Tetris story

The story of Tetris didn’t start in a corporate boardroom but in the quiet of a Moscow office, where a young researcher, Alexey Pajitnov, shuffled abstract shapes in his head as easily as others shuffle a deck. On an Electronika‑60 he pieced together a simple, almost meditative puzzle: blocks fall, you catch the rhythm, line them up — and at some point you realize the game has already taken over your fingers. The name sprang from a mash‑up of tetrominoes and tennis — "Tetris." Clean, punchy, a little Soviet‑austere and irresistibly playful. That’s how the "falling blocks game" was born — the one people would simply call Tetris, the "Soviet Tetris," and, yes, fondly, "Tetrishka."

From canteen chatter to global fever

At first it was almost an in‑joke among academics: they passed early builds on floppies, argued over tea about how best to spin the I‑piece and where to tuck the S/Z "snake." Student Vadim Gerasimov polished it up and ported it to the IBM PC, and suddenly the "history of Tetris" wasn’t just a Moscow thing. Copies spread like good rumors — from institute hallways to companies abroad. In Budapest, developers spotted it, picked up the idea, and with them came people who knew how to turn ideas into contracts and a box on a store shelf.

Then the adventure took on a dash of detective drama. British entrepreneur Robert Stein hurried to "secure the rights" without fully grasping who actually owned them. In the USSR, software exports went through ELORG, and the Soviet side had its own view on this strange new kind of deal. Words like "license" and "console rights" echoed in meeting rooms more often than "lines" and "points." And yet there was one person who didn’t just see a document — he saw a game that belonged in every home.

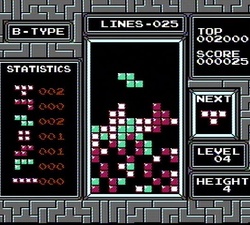

How Nintendo’s Tetris found its way to the NES

Henk Rogers, head of Bullet‑Proof Software, spotted Tetris at a trade show and caught the big truth: here was that rare "instant‑read" puzzle that needs no manual. He flew to Moscow, met Pajitnov, and helped ensure Nintendo would get the console rights. That’s how "Nintendo’s Tetris" landed on the NES — the machine that, in the late ’80s, turned living rooms into tiny arcades.

The road wasn’t smooth. In parallel, Atari Games, via its Tengen label, shipped its own NES version — unlicensed by Nintendo. Suddenly there were two Tetrises on one platform: the official gray cartridge and Tengen’s stealthy black cart. The courts sorted it quickly: console rights belonged to Nintendo, and Tengen had to pull its game from shelves. To players it felt like an urban legend — there was a "forbidden Tetris" that vanished. But the screen kept the real truth: falling blocks and that spark of magic when a line clears and your heart skips a beat.

A melody you can’t mistake for anything else

On NES, Tetris found its voice. The folk tune "Korobeiniki" — labeled Type A in the menu — became a chiptune anthem. A simple melody turned into a full‑on thumb workout, a sporting march for the D‑pad. Ever since, the first notes are enough and your brain is already drawing the square and the L‑piece, begging to be slotted into place. It’s that rare case where music and gameplay fuse so tightly you can’t hear or see one without the other.

Why did this "Tetris on Dendy" — that’s what many in our neck of the woods called the NES and its clones — win so many hearts? Because it offers a fair, crystal‑clear goal: order. In a world that wants to scatter, here you’re the steward of falling chaos. You cradle the I‑piece and prep a well for it in advance, snake an S into a tight channel, make peace with the whims of the T‑piece — and suddenly you hit that working flow state where thoughts move without effort. Years later it would be dubbed the "Tetris Effect," but back then it was just the feeling that the game "sits in your hands" and won’t let go.

It’s wild how fast "Soviet Tetris" became a global game. It rode through ELORG’s bureaucracy to the U.S. and Japan, changed publishers — from Bullet‑Proof to Nintendo — survived Nintendo vs. Tengen, and then slipped just as easily into living rooms and dorms. At home it was the "line game," "Tetris on the Dendy"; abroad it stood as proof that a great core mechanic beats everything else. And the conversation sounded the same everywhere: "So, going for one more line?"

One more brushstroke. "Alexey Pajitnov’s Tetris" is that rare moment when the designer’s love of puzzles, the persistence of people like Henk Rogers, and the stubbornness of companies wrestling over licenses converged. On NES, that point snapped into perfect focus. No garnish — just falling tetrominoes, score, speed, and music. That’s why "Nintendo’s Tetris" felt like a pure distillation of the idea. Morning — one warm‑up run; evening — "one more round, then bed." And then you catch yourself stacking books on a shelf just to "complete a line."

That’s the answer to the big question: what made it beloved? Clarity. That tiny joy of order Tetris delivers the instant the screen flashes, the row dissolves, and the familiar effect pops in your speakers. Each time you’re sure this will be the perfect run — no holes, a clean wall, the I‑piece sliding in like butter. That faith, poured into a gray NES cartridge, is what made the game immortal.